Last week I interviewed Brian Czech about the relationship between economics and the planet’s biosphere and one viable solution: steady state economics, an economic model which prioritises stability and the protection of planetary boundaries.

During the episode, Brian introduced me to the trophic theory of money, an important theory which essentially rubbishes the notion of techo-utopic solutions to the climate crisis being a viable option.

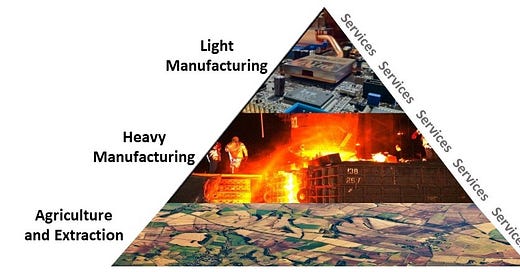

The Tropic theory of money states that it is the agricultural surplus at the bottom of the pyramid which frees up the hands necessary to work in heavy industry, which themselves create the possibility of light industry. In other words, we have a surplus of food and labourers who can use heavy machinery which in turn manufacture more complex machines, which then create algorithms etc which define the complex and ultra-modern world many live in around the planet.

So as technology becomes more complex, we have to go through each stage of the pyramid in order to access it, we cannot just get to complexity while skipping the lower rungs. Now, that means the more rungs or layers we add to the pyramid, the larger that bottom layer must become. The bottom layer represents the expansion of agriculture and extractive industries like logging and mining.

So we will always need more land to create the agricultural surplus which will enable the creation of more of the heavy machines, which can create more of the lighter machines, which can create more of the complex technology that people believe will help us navigate through the crisis.

Ultimately, what that means is more and more natural resources are going towards solving the problem—which is actually creating the problem.

Brian says environmental destruction and the economy are tied at the hip, as is environmental destruction and technological progress. What the Center for the Advancement of the Steady State Economy advocate for is that the global north’s economy contract for a time as the global south’s grows, and then mutually plateau to what they call steady statesmanship.

This would be an act of international diplomacy, essentially, for us all to steward the land and look after one another.

This is very much like de-growth, but rather than continuing to degrow there is a plateau, which means the economy would have a built in redistribution function with both materials and energies rationed and prioritised.

Now, it’s the prioritisation which is the fundamental part of this plan. During the episode, Brian talks about the fact that our technological rate of progress would have to slow because we cannot continue using resources—exploiting resources—at the same rate for technological advancement, an advancement that he says has actually been getting increasingly difficult as things become more complex; we've eaten much of the low hanging fruits of technological advancement and so progress isn’t as fulfilling or rewarding as it once was.

So the rate of progress is going to have to decrease. Brian imagines that technological progress will be more akin to artistic collaboration. So when a community needs something, they will collectively envisage a new piece of technology that may help themselves and other communities around the world.

However, if this the steady state economy is an act of international diplomacy, then this means states would have more control over the economy and over technology, and therefore could allocate energy rations to scientists in order to prioritise the advancement of certain necessities. This would punctuate the steady state economy with the growth of particular things in moments of crisis, the COVID vaccine being an excellent precedent for such organisation. This would demand managing our resources—energy and finance—to prioritise the accelerated growth of necessary advancements (both in emergencies and as pre-meditated strategy) in order to navigate through the world with a longterm eye on the future.

Economic models like the steady state economy or degrowth don’t mean, then, that progress would stop. On the contrary, progress would be the legitimate and managed reflection of what humanity needs rather than a label used to justify profit maximisation.

Progress would become wise. It would demand we take the time to think about what we need, both now and in the future, and respond to those needs in coordination with the biosphere’s needs. It would demand divorcing want from need, which in itself would demand a level of self-reflection that, whilst troubling, could only result in better lives for everyone. For how many amongst us truly understand what constitutes a good life?

Capitalism takes all of our decisions away. Economic growth takes all of our decisions away. People scramble to push forward in whatever corner of the market is left. And because everything is constantly growing and all of those resources are being exploited in order to constantly grow, you’re scrabbling with scarcity in mind. Everyone’s a loser in a society where winner takes all; imagine if, rather than forests, we had singular bloated trees whose roots tore up the earth and branches blocked out the sun.

What's so exciting about the idea of a steady state economy that is punctuated by managed growth is that it gives us back our choices. If we have lots of energy and resources available to us, in theory, and can do almost anything we want, it then becomes very exciting to choose what we do, to take ownership over the direction of mankind, rather than just rapidly bloating in all directions.

To hand-select a few directions and perfect them, to do them well, through the accumulated and collective knowledge of what we know about our planet and what we then learn about ourselves, to become the master of ourselves, not the earth. That seems like a very exciting future indeed.

“To hand-select a few directions and perfect them, to do them well, through the accumulated and collective knowledge of what we know about our planet and what we then learn about ourselves, to become the master of ourselves, not the earth. That seems like a very exciting future indeed.”

Yes. Good.

Next task:

Who decides?

Who decides who decides?

How do we hold the deciders accountable for the decisions that they make?

Always prefer your condensed version of the conversation to the conversation itself.